|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

2181 BC

|

2040

|

1782

|

1570

|

1070

|

525

|

332

|

30 BC

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

New Kingdom

In the New Kingdom (1570-1070 BC), during the reign of Tuthmosis IV (1419-1386

BC) of the 18th Dynasty, the role of

shabtis changed. They were then regarded as deputies for the deceased. Agricultural

implements were now included as part of their iconography, either painted

directly onto the figure or incorporated in the modelling. These implements

include a pick, a hoe, seed baskets, water pots carried on a yoke, and

sometimes brick moulds. Many of the figures are inscribed with the

shabti spell stipulating their agricultural duties. The shabtis were often made in stone or wood, the latter sometimes with attractive

polychrome decoration similar to coffins of the period. The use of faience

increased in popularity.

During the brief interlude in the New Kingdom known as the Amarna Period

(1350-1334 BC) Akhenaten introduced a new monotheistic religion based on the

worship of the sun disc, the Aten. The few surviving

shabtis for private persons have softer features reflecting the more restrained art of

the time. Akhenaten

’s shabtis, mostly fragmentary, show they were not provided with agricultural tools.

Instead he chose the ankh-sign, symbol of life, or the crook and flail, symbols

of kingship. The king is not regarded as an Osiris in the inscriptions. Some

private

shabtis are inscribed with a unique formula invoking the Aten through which resurrection

was to be obtained. However, they still retain the more usual implements. Thus

the role of

shabtis at this time is not clear. It was Tutankhamen who was responsible for

reinstating the old religious ideology of earlier times.

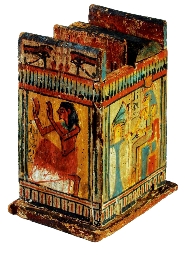

By the early 19th Dynasty a new type of figure was introduced alongside the

other

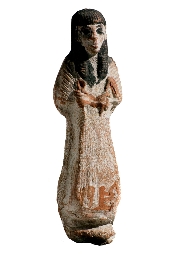

shabtis. These show the deceased wearing the dress of daily life with the

characteristic short-sleeved tunic, kilt and triangular apron. They wear a

bipartite or duplex wig

(1). The number of shabtis placed in burials gradually increased during the New Kingdom and reached

perhaps as many as 10 by the early 19th Dynasty with the number increasing

still further thereafter. Wooden

shabti boxes or pottery shabti jars were introduced as a means of storing the figures in the tomb. The wooden

boxes were often beautifully painted

(2).

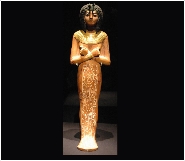

Although no royal shabtis have been found before the reign of Ahmose, the first king of the 18th Dynasty

(1570-1546 BC), it is evident that royal burials contained a considerably

larger number of

shabtis than the nobility. 88 shabtis made in a variety of materials were found in the

tomb of Amenophis II. About 60

shabtis are known for Amenophis III and there are numerous fragments of shabtis for Akhenaten. Tutankhamen was buried with 417 shabtis, including many of

outstanding quality

(3). Seti I appears to have had in excess of 700 shabtis, the largest number for a New Kingdom pharaoh, although the majority of these,

made in wood, are fairly rudimentary in their execution

(4).

A group of shabtis peculiar to the New Kingdom, 20th Dynasty are those referred to as ‘contours perdus,’ literally meaning ‘lost contour’. They are always made of alabaster and often have details added in coloured

wax. Their shape is always very simple and the feet taper to a point. Several

of the Ramesside kings had this type of

shabti, including Ramesses IV (5), V, VII, IX and X. The simplistic outline and shape, even in royal examples,

probably reflects the general decline in Egypt following the reign of Ramesses

IV when the country became unstable with a succession of weak rulers. Other

shabtis of this type are also found for private individuals and there are also

anonymous examples.

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

1. Polychrome terracotta shabti for S-?? wearing the dress of daily life

New Kingdom, 19th Dynasty

c. 1185-1070 BC

ex Gustav Moustaki collection

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

2. Polychrome wooden shabti box for Pa-en-pa-khenty

New Kingdom, 19th Dynasty

c. 1293-1185 BC

ex Horace Owen collection

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Photo: Bob Partridge

Editor, Ancient Egypt magazine

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

3. Wood with gold foil shabti for Tutankhamen

From Thebes, Valley of the Kings

(KV 62)

New Kingdom, 18th Dynasty

c. 1334-1325 BC

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

4. Fragmentary faience shabti for Seti I

Probably from Thebes, Valley of the Kings (KV 17)

New Kingdom, 19th Dynasty

c. 1291-1278 BC

ex Gustav Moustaki collection

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

5. Alabaster ‘contours perdus’ shabti for Ramesses IV with details added in black painted and wax

Probably from Thebes, Valley of the Kings (KV 2)

New Kingdom, 20th Dynasty

c. 1151-1145 BC

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|